Ox Herding Pictures (Free Preview)

Module 03: The Core Teachings > Ox Herding Pictures > Video Intro

Introduction

Maps, pop quizzes, and guideposts can be infinitely helpful when we undertake any spiritual journey. The path to self-discovery is not only the most harrowing of undertakings, it takes immense courage to make the choice to examine oneself honestly and completely. Most actually avoid self-examination at all costs, and the world we live in is becoming incredibly efficient at providing us with more and more distractions with every new gadget, every new and improved screen or app or groundbreaking snippet of information that we absolutely must talk about and pass onto anyone who will listen, assisting us from ever having to sit with our selves, even for a moment.

What we find when we truly sit with ourselves, is the answer to our frustration, our agitation and our discontent; it’s our Original Mind that’s been buried under years of conditioning and distraction. It’s the place where genuine, unshakable happiness truly does exist. Sadly, though, being face to face with our own perfection is something we’ve been conditioned to feel ashamed of instead of allowing it to guide and empower us.

The path to self-discovery, by its very nature, is rooted in self-doubt, dissatisfaction, and confusion. So often, the path is unclear, there seem to be so many forks in the road that force us to choose, or we’re not exactly sure which way to turn, afraid of not making the “right” decision. Thankfully, though, this “not-knowing” illustrates the exact problem we’re trying to overcome. When we are not in touch with our True Nature, there is only doubt, seething dissatisfaction, of emptiness, and a feeling as though we should know true joy, but don’t, except perhaps in rare glimpses.

Therefore, the more indicators that we have to help illuminate our path, the better. And, believe it or not, every word that has ever been written in relation to Buddhism, Zen, the Tao; they are nothing more than guideposts to our own journey. Despite the unfamiliar terminology that is sometimes used with our training, there is no information within them that we do not already possess.

The Ox Herding photos are one of those beautifully crafted guideposts on our path. This series of images helps us to visualize the core teachings. Just like the Tao Te Ching, the Ox Herding Pictures can provide an endless source of inspiration for the student of Zen. It’s something we can return to time and again to remind ourselves of the path we are now on, where exactly we are on that path, or as a reminder of the difficult path we’ve taken and now embody in our daily practice.

History of the Ox Herding Pictures

There have been many manifestations, many versions, but I still prefer the set drawn by Tenshō Shūbun (天章周文) who lived from 1414-1463. It’s a series of 10 circular paintings mounted as a hand scroll, all in ink with some light color on parchment. As many others have, I’ve often thought of trying to modernize this series, but I believe that even today, the images and their accompanying refrains are equally as relevant. I offer commentary on each panel to help update and modernize the message for you.

A very useful exercise is to write your own commentary for each of the Ox Herding panels. When you come to a panel you’re having difficulty commenting on, it’s another way to know exactly where on the path to self-discovery you are./

The original author of “Ox Herding Pictures” was a Zen master of the Sung Dynasty known as Kaku-an Shi-en of the Rinzai school of Zen. In his general preface, though, he refers to another Zen Master called Seikyo, who made use of the ox to explain his Zen teaching. In Seikyo’s 5 picture series, the gradual development of the Zen life end in the disappearance panel. This image is now the eighth picture of the series, and is called “The Ox and the Man Both Gone out of Sight”; something you will learn about in detail in “Module 07: Cultivating Emptiness“. Kaku-an felt ending on Emptiness was somewhat misleading, because it made it seem as though Cultivating Emptiness was the ultimate goal of Zen discipline, which it is not.

So, he expanded on the 5, to the 10 most study and refer to today.

Kaku-an’s series is accompanied by my favorite depictions of the Ox Herding images by Shubun, a Zen priest of the fifteenth century. The original pictures are preserved at Shokokuji, Kyoto.

The passages below were translated into English by D.T. Suzuki, and the poems were translated by John Daido Loori. Two of D.T. Suzuki’s most famous books are “Introduction to Zen Buddhism” and “Manual of Zen Buddhism”. John Daido Loori has authored a number of books, but the one most relevant to this lesson is his . I highly recommend checking them out as you progress through this course.

Ox Herding Photos & Commentary

Onto the Ox Herding photos and commentaries. The translation is first, followed by the corresponding image, and then my commentary.

I. Searching for the Ox.

The beast has never gone astray, and what is the use of searching for him? The reason why the oxherd is not on intimate terms with him is because the ox herder himself has violated his own inmost nature. The beast is lost, for the ox herder has himself been led out of the way through his deluding senses. His home is receding farther away from him, and byways and crossways are ever confused. Desire for gain and fear of loss burn like fire; ideas of right and wrong shoot up like a phalanx.

Alone in the wilderness, lost in the jungle, the boy is searching, searching!

The swelling waters, the far-away mountains, and the unending path;

Exhausted and in despair, he knows not where to go,

He only hears the evening cicadas singing in the maple-woods.

II. Seeing the Traces.

By the aid of the sutras and by inquiring into the doctrines, he has come to understand something, he has found the traces. He now knows that vessels, however varied, are all of gold, and that the objective world is a reflection of the Self. Yet, he is unable to distinguish what is good from what is not, his mind is still confused as to truth and falsehood. As he has not yet entered the gate, he is provisionally said to have noticed the traces.

By the stream and under the trees, scattered are the traces of the lost;

The sweet-scented grasses are growing thick–did he find the way?

However remote over the hills and far away the beast may wander,

His nose reaches the heavens and none can conceal it.

III. Seeing the Ox

The boy finds the way by the sound he hears; he sees thereby into the origin of things, and all his senses are in harmonious order. In all his activities, it is manifestly present. It is like the salt in water and the glue in color. [It is there though not distinguishable as an individual entity.] When the eye is properly directed, he will find that it is no other than himself.

On a yonder branch perches a nightingale cheerfully singing;

The sun is warm, and a soothing breeze blows, on the bank the willows are green;

The ox is there all by himself, nowhere is he to hide himself;

The splendid head decorated with stately horns what painter can reproduce him?

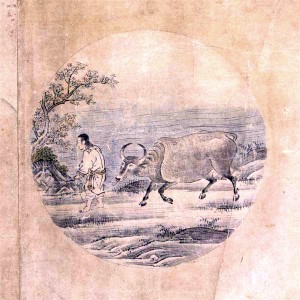

IV. Catching the Ox

Long lost in the wilderness, the boy has at last found the ox and his hands are on him. But, owing to the overwhelming pressure of the outside world, the ox is hard to keep under control. He constantly longs for the old sweet-scented field. The wild nature is still unruly, and altogether refuses to be broken. If the ox herder wishes to see the ox completely in harmony with himself, he has surely to use the whip freely.

With the energy of his whole being, the boy has at last taken hold of the ox:

But how wild his will, how ungovernable his power!

At times he struts up a plateau,

When lo! he is lost again in a misty impenetrable mountain-pass.

V. Taming the Ox

When a thought moves, another follows, and then another-an endless train of thoughts is thus awakened. Through enlightenment all this turns into truth; but falsehood asserts itself when confusion prevails. Things oppress us not because of an objective world, but because of a self-deceiving mind. Do not let the nose-string loose, hold it tight, and allow no vacillation.

The boy is not to separate himself with his whip and tether,

Lest the animal should wander away into a world of defilements;

When the ox is properly tended to, he will grow pure and docile;

Without a chain, nothing binding, he will by himself follow the ox herder.

VI. Riding the Ox Home

The struggle is over; the man is no more concerned with gain and loss. He hums a rustic tune of the woodman, he sings simple songs of the village-boy. Saddling himself on the ox’s back, his eyes are fixed on things not of the earth, earthy. Even if he is called, he will not turn his head; however enticed he will no more be kept back.

Riding on the animal, he leisurely wends his way home:

Enveloped in the evening mist, how tunefully the flute vanishes away!

Singing a ditty, beating time, his heart is filled with a joy indescribable!

That he is now one of those who know, need it be told?

VII. The Ox Forgotten, Leaving the Man Alone

The dharmas are one and the ox is symbolic. When you know that what you need is not the snare or set-net but the hare or fish, it is like gold separated from the dross, it is like the moon rising out of the clouds. The one ray of light serene and penetrating shines even before days of creation.

Riding on the animal, he is at last back in his home,

Where lo! the ox is no more; the man alone sits serenely.

Though the red sun is high up in the sky, he is still quietly dreaming,

Under a straw-thatched roof are his whip and rope idly lying.

VIII. The Ox and the Man Both Gone out of Sight

All confusion is set aside, and serenity alone prevails; even the idea of holiness does not obtain. He does not linger about where the Buddha is, and as to where there is no Buddha he speedily passes by. When there exists no form of dualism, even a thousand-eyed one fails to detect a loop-hole. A holiness before which birds offer flowers is but a farce.

All is empty-the whip, the rope, the man, and the ox:

Who can ever survey the vastness of heaven?

Over the furnace burning ablaze, not a flake of snow can fall:

When this state of things obtains, manifest is the spirit of the ancient master.

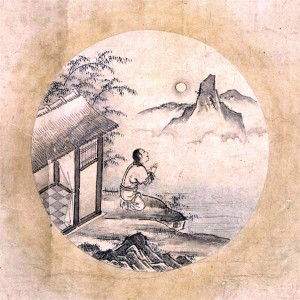

IX. Returning to the Origin, Back to the Source

From the very beginning, pure and immaculate, the man has never been affected by defilement. He watches the growth of things, while himself abiding in the immovable serenity of non-assertion. He does not identify himself with the maya-like transformations [that are going on about him], nor has he any use of himself [which is artificiality]. The waters are blue, the mountains are green; sitting alone, he observes things undergoing changes.

To return to the Origin, to be back at the Source–already a false step this!

Far better it is to stay at home, blind and deaf, and without much ado;

Sitting in the hut, he takes no cognizance of things outside,

Behold the streams flowing-whither nobody knows; and the flowers vividly red-for whom are they?

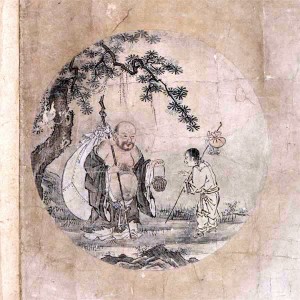

X. Entering the City with Bliss-bestowing Hands

His thatched cottage gate is closed, and even the wisest know him not. No glimpses of his inner life are to be caught; for he goes on his own way without following the steps of the ancient sages. Carrying a gourd[1] he goes out into the market, leaning against a staff[2] he comes home. He is found in company with wine-bibbers and butchers, he and they are all converted into Buddhas.

Bare-chested and bare-footed, he comes out into the market-place;

Daubed with mud and ashes, how broadly he smiles!

There is no need for the miraculous power of the gods,

For he touches, and lo! the dead trees are in full bloom.